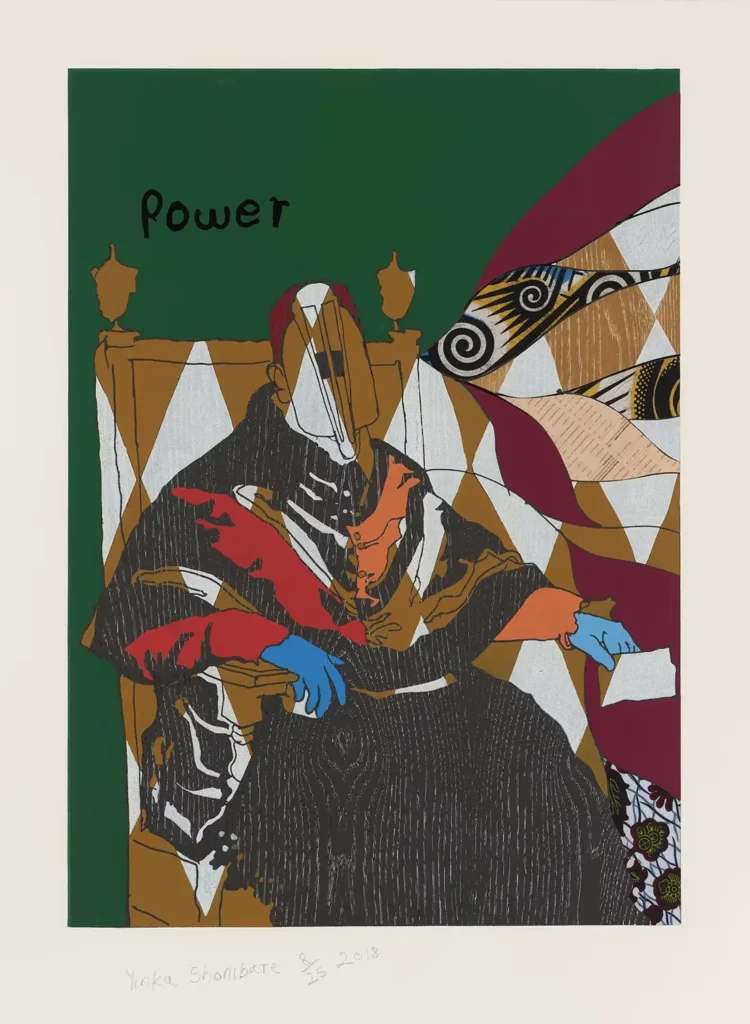

Yinka Shonibare explores colonialism, authenticity, identity, and power relations through his paintings, photographs, videos, and installations. Raised speaking Yoruba and immersed in British and American media, Shonibare’s work reflects a blend of influences and a questioning of cultural purity.

Born in London in 1962, Shonibare was struck by transverse myelitis early in his art school journey, leading to paralysis on one side of his body and a permanent disability. An art teacher’s challenge on why he did not create “authentic African art” prompted him to explore the concept of authenticity and the significance of his multicultural upbringing.

Shonibare’s Artistic Style

Shonibare’s sculptures draw heavily from art history, especially Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s work, showcasing scenes of opulence and privilege through idyllic, romantic narratives alongside imagined tales of decadence and violence.

A hallmark of his art is the use of batik fabric, which he utilizes to create vivid costumes for his sculptures. This juxtaposition of traditional and contemporary elements is striking. Headless mannequins clad in these outfits do represent the diminishing sense of a collective identity for him in the current global society.

Shonibare’s Symbolism

On the one hand, Shonibare makes use of the fabric for its distinctive and symbolic link to West African societies and culture. On the other hand, he is drawn to the fabric for its complex, multi-cultural history; it was first mass-produced in Holland, inspired by Indonesian Batik designs, and then sold on to West Africa in the 19th century from Europe where, to be a commercial success, it needed to reflect African tastes, aesthetics, proverbs, culture and patronage.

To this day, the authentic Vlisco brand fabrics have remained popular in African fashion and beyond, but are still manufactured in the Netherlands. These fabrics are now worn on the African continent as shirts, pants, dresses, skirts, and head wraps. Hence this vivid textile also became a symbol of the postcolonial global market and of wealth. Shonibare’s exploration of these postcolonial themes parallels the work of Nicole Eisenman, who also delves into the complex narratives of identity and culture in contemporary art.

The entangled history gives the fabric a complexity which Shonibare relates to his own identity, as both British and African, highlighting how cultural signifiers are never as straightforward as they might seem.

Shonibare’s Themes

Shonibare regularly alludes to historical occurrences, personalities, and stories in his artwork, especially those that deal with colonialism and its aftereffects. He challenges traditional views and invites viewers to reevaluate history from other angles by reimagining historical situations and personalities in a contemporary setting.

Shonibare’s incorporation of Victorian-era silhouettes introduces an additional dimension of complexity to his art. These silhouettes, evoking the British colonial era, stir up feelings of nostalgia and alienation.

Using objects, symbols, and imagery from several cultural traditions, he subverts accepted ideas of cultural authenticity and emphasizes the hybrid character of modern identity. He invites viewers to ponder the implications of this fictional figure’s dual identity and the complexities it represents.

Shonibare’s work frequently combines comedy, irony, and playfulness, even when it tackles serious subjects. He challenges viewers to think critically about the topics he addresses by using satire and subversion to attack social standards, power systems, and prejudices.

Shonibare’s Early Works

Shonibare began his artistic journey with a deep dive into material and form experimentation, aiming to express his intellectual ideas uniquely. Initially, he created vibrant paintings with figures in colorful clothes, which led him to explore textiles and materials in his sculptures and installations.

Deeply engaged with colonial histories, especially the British colonization of Nigeria, Shonibare’s early works often referenced colonial aesthetics and symbols, encouraging viewers to reflect on the complexities of colonial legacies. He also showed an early interest in cultural hybridity and global cultural interconnectedness, challenging traditional views of cultural authenticity by mixing elements from various cultures.

It was in 1989 that he had his first solo exhibition at the Byam Shaw Gallery in London. He then continued to study at Goldsmiths in London, earning his MFA in 1991. Back in 1999, Shonibare introduced “Dysfunctional Family,” a collection of four sculptures with an otherworldly vibe, portraying a mother-daughter duo in serene white and blue tones, and a father-son pair in vibrant red and yellow hues.

Shonibare was notably commissioned by Okwui Enwezor at documenta XI in 2002 to create his most recognized work, Gallantry and Criminal Conversation, which launched him on the international stage.

Sexuality and ethical ideals provided Shonibare with a plethora of material for his works during documenta XI, culminating in the enormous Gallantry and Criminal Conversation. This composition was inspired by the Grand Tour, a customary travel route that young nobility found appealing in the 17th and early 18th centuries.

At the Venice Biennale, his series Refugee Astronaut (2015-ongoing) introduced a life-sized nomadic astronaut adorned with “African” fabric, equipped to navigate ecological and humanitarian crises. Carrying a mesh sack filled with worldly possessions, the figure symbolizes the challenges of displacement.

Originating from Shonibare’s contemplation of space as a potential refuge, the artwork serves as a cautionary tale on environmental negligence and capitalism, challenging the unsustainable pursuit of perpetual growth. It also subverts colonial connotations, presenting a refugee astronaut in stark contrast to the colonial instinct of conquering the world.

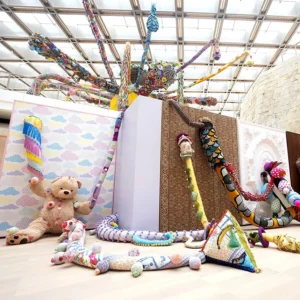

Shonibare was included in a major mid-career survey conducted in Australia and the USA in 2008–09. The show began in Sydney at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), went to New York’s Brooklyn Museum in June 2009, and then ended up in October 2009 at the Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of African Art in Washington, DC. For the 2009 Brooklyn Museum exhibition, he created a site-specific installation titled “Mother and Father Worked Hard So I Can Play”, which was on view in several of the museum’s period rooms.

Shonibare’s Photography and Film

In addition to creating provocative sculptures, Shonibare has worked in a number of mediums, including cinema.

In such works as Diary of a Victorian Dandy (1998), Shonibare created a series of photographs featuring himself as a dandy in a variety of tableaux. He also portrayed the protagonist of an Oscar Wilde novel in the photographic series Dorian Gray (2001).

Many of Shonibare’s works made reference to paintings by earlier artists, among them Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Francisco Goya, and Leonardo da Vinci. In the 21st century Shonibare expanded his repertoire of techniques to include films Un ballo in maschera (2004) and Odile and Odette (2005).

His 2011 video work “Addio del Passato” explores themes of love, sorrow, and memory in a moving way. The film, which drew inspiration from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera “La Traviata,” highlights the universality of emotional experiences regardless of cultural background with its protagonist dressed in clothes made of Dutch wax fabric.

Shonibare’s Awards and Merits

Over his career, Shonibare has won many important honors. Widespread praise for Shonibare’s work may be shown in his 2004 nomination for the Turner Prize, which saw him gain a sizable amount of popular support for his exhibitions. He made the short list for the London’s Stephen Friedman Gallery solo exhibition in 2004. He was the most popular nominee that year among the four; according to a BBC internet poll, 64% of respondents thought highly of his work. His incorporation of the title of Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) into his artistic persona and resume demonstrates his sensitive and careful commitment to addressing historical and societal issues.

Among his accolades are the 2019 designation as a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) and the 2013 induction as a Royal Academician at The Royal Academy. Shonibare became the eighth recipient of the Whitechapel Gallery Art Icon Award in March 2021, which was given in recognition of his noteworthy achievements to the art world.

Shonibare’s Current and Upcoming Shows

Jorge M. Pérez Collection showcases never-before-seen textile works, serving as focal points for interdisciplinary dialogue in the exhibition To Weave the Sky. The pieces serve as central themes for creative conversations with artworks in different mediums and feature works from over 100 artists from around the globe. This showcase draws inspiration from weaving’s ties to abstraction, geometry, landscapes, and indigenous rituals.

Shonibare participated in the Venice Biennale with Stranieri Ovunque – Foreigners Everywhere, exploring contemporary artistry in the Central Pavilion and Arsenale.

His latest solo exhibition, Suspended States, at Serpentine South, London, offers a nuanced exploration of history, asylum, and humanitarian aid until September 1, 2024. This exhibition examines the effects of power structures on asylum sites, the controversy surrounding public monuments, the environmental impact of colonialism, and how colonial legacies influence conflict and peace initiatives.

Notable works include two significant new installations: “Sanctuary City” (2024), which uses miniature buildings to represent places of refuge, and “The War Library” (2024), featuring 5,000 books in Dutch wax print that discuss conflicts and peace treaties both delving into the impact of power structures on refuge sites and colonial legacies on global conflicts.

Shonibare: An Icon of Multiculturalism

Yinka Shonibare’s work powerfully reflects on identity, colonialism, and cultural interchange. Overcoming physical challenges, he delves deeply into multiculturalism and authenticity, shaping his provocative art in various forms. His sculptures, dressed in Dutch wax-print fabrics, question historical narratives and power imbalances, urging a reevaluation of cultural authenticity and social norms.

Shonibare uses materials and themes, like the complex history of batik fabric, to highlight global cultural interconnectedness. His playful yet critical approach to historical references adds depth, encouraging a reexamination of societal structures and biases. Exhibiting in renowned institutions globally, Shonibare captivates with his work, providing insightful commentary on the human condition, and our world.