The Biennale charts intricate narratives, delving deep into marginalized identities and the layers of art institutions, confronting the myriad challenges in the world, evoking both pleasure and unease. Explore the most compelling and rich survey of contemporary art with our curatorial analysis and highlights from the national pavilions.

The main exhibition features 331 artists, with a focus on Global South representation, including Indigenous, queer, and marginalized artists, as well as those from the Italian Diaspora. Curator Adriano Pedrosa sheds light on historical artists and boosts the presence of Asian artists compared to past editions.

Curatorial strategies echo a commitment to rewriting art history, breaking geographical hierarchies, and amplifying diverse voices, evident in historical sections featuring non-Western artists. Collaboration and collective memory emerge as central themes, intertwining with nuanced political commentary amidst the market pressures and political constraints artists grapple with.

The exhibition features moments of symmetry and visual correspondence, notably highlighted by two expansive murals at each end of the Corderie, a former rope-making factory in the Arsenale. It includes Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s “Rage is a Machine in Times of Senselessness” and the Bangalore collective Aravani Art Project’s “Diaspore,” which both encapsulate themes of foreignness, queerness, indigeneity, and outsider art, meticulously curated by Pedrosa.

Artists boldly challenge the colonial narrative entrenched within museums through thought-provoking works like Glicéria Tupinambá’s plea for cultural object repatriation, Sandra Gamarra’s “Migrant Art Gallery,” and Pablo Delano’s “The Museum of the Old Colony.”

Father Santiago Yahuarcani and son Rember’s works illustrate an evolution in language, with Santiago using paper and Rember canvas, each conveying activism about Indigenous rights and environmental issues. Another motif is textiles, exemplified by Dana Awartani’s large silk pieces representing heritage destruction, and the Mataaho Collective’s woven canopy symbolizing a womb-like space at the Arsenale.

Here are our highlights from the national pavilions:

Brazil stands out for its focus on ongoing exploitation of the Global South. In her installation “Equilíbrio” (Balance, 2020–24), Glicéria Tupinambá displays a monitor atop a pile of dirt showing fires in Tupinambá territories, highlighting the destruction caused by landowners.

While addressing colonialism, Tupinambá primarily focuses on modes of self-preservation, such as showcasing Tupinambá community members sewing nets for fishing. The installation “Dobra do tempo infinito” (Fold of Infinite Time, 2024) provides an immersive experience akin to entering a sanctum, reflecting Tupinambá’s emphasis on resilience and cultural preservation.

Great Britain showcases John Akomfrah’s expertise in unraveling grand postcolonial narratives through multipart film installations. Akomfrah’s latest project, “Listening All Night to The Rain,” overwhelms visitors with numerous screens displaying hours of footage accompanied by independent sound.

The artist deliberately creates an immersive experience that is nearly impossible to fully absorb in one visit. The installation intertwines diverse narratives, including the experiences of the Windrush Generation, the Mau Mau uprising in Kenya, Rachel Carson’s environmental writings, the Vietnam War, and ecological concerns, suggesting interconnectedness among struggles facing the Global South.

Japan’s pavilion stands out as the quirkiest, showcasing sculptor Yuko Mohri’s inventive creations. Mohri’s installations consist of makeshift gadgets crafted from piping and discarded materials, which awkwardly manipulate water to set off cymbals and chimes intermittently. Every component, from fans to pans, is sourced from nearby shops, contrasting with the Biennale’s pursuit of perfection.

Mohri finds beauty in the imperfections and failures of systems, drawing inspiration from makeshift repairs in the Tokyo subway. Even light bulbs attached to wires are allowed to fall through the pavilion’s floor, inviting observers to glimpse the complexities beneath its polished exterior.

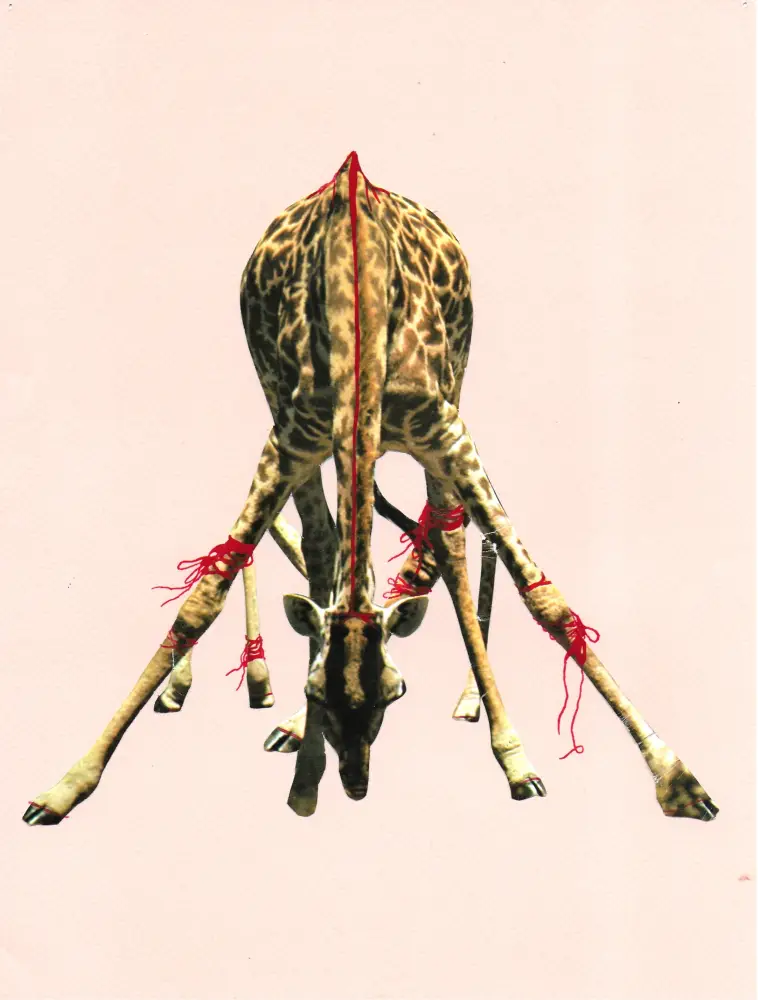

The Czech Pavilion by Eva Koťátková features a conceptual artwork centered around a cut-up giraffe, representing Lenka, who lived briefly in a zoo before her death. The installation aims to provide Lenka with a more humane existence and reflects on colonialism’s impact. Despite its serious themes, children play inside the giraffe’s structure, seemingly unaware of its backstory. The installation prompts viewers to see Lenka as an equal, inspiring reflection on humanity’s relationship with animals.

The Nigerian Pavilion features diverse artworks representing the Nigerian diaspora. The pavilion serves as a glossy statement on invisible memories shaping the Nigerian diaspora, with artists of Nigerian descent, yet not based in the country, contributing significantly.

Precious Okoyomon’s installation, reminiscent of a makeshift radio tower, explores the idea of a Nigeria existing beyond its borders.

Toyin Ojih Odutola presents figurative paintings inspired by Igbo shrine-like structures, while Onyeka Igwe revisits work about a British-run production company in Lagos.

Abraham Oghobase’s photography, notably “Colonial Self-Portrait 05,” blurs historical images, prompting reflection on inherited memories.

The German Pavilion challenges the concept of nationhood by exploring in-between spaces and disparate locations. In the Giardini, Ersan Mondtag covers the facade in dirt, while Yael Bartana presents a video on space travel rooted in the Book of Isaiah. On La Certosa island, less frequented by visitors, sound artworks emit eerie frequencies and tree noises.

Nicole L’Huillier’s piece, featuring microphones sandwiched between plastic sheets draped over branches, stands out. Divided into two parts, the pavilion offers a unique experience that transcends traditional national presentations, signaling a potential evolution in the Biennale’s format.