The Toronto Biennial of Art, titled Precarious Joys, features 55 artists at 12 locations throughout the city. The exhibition highlights the fragility of contemporary life while celebrating art as an agent of change, exploring the risks of visibility related to citizenship, Indigenous erasure, climate disaster, and gentrification.

The Toronto Biennial is still in its early stages, having held only three editions in ten years, which poses the challenge of weaving the city’s less obvious artistic history into a global context.

The title draws inspiration from Chilean poet and artist Cecilia Vicuña’s ongoing series Precarious Objects, which she began in the mid-1960s. This series, consisting of delicate sculptures made from manmade and natural debris left exposed to the elements.

The curatorial themes—’Joy’, ‘Precarious’, ‘Home’, ‘Polyphony’, ‘Solace’, and ‘Coded’—invite exploration of collective histories, queer and feminist perspectives, environmental justice, sovereignty, migration, spiritual wisdom, and resilience.

The exhibition avoids grand spectacles and is light on provocation and material excess, aligning with recent trends seen in other biennials. Instead, it features traditional art forms like weaving, dance, and song, along with baked goods.

At the entrance of the Biennial’s main venue at 32 Lisgar Street, several of Cecilia Vicuña’s Precarious Objects are installed as a symbolic opener, setting a poetic tone for the exhibition.

Leila Zelli’s installation Un chant peut traverser l’océan (2023–ongoing) features shapes stamped on the wall, representing Iranian women waving their hijabs in defiance. Her two-screen video installation, Pourquoi devrais-je m’arrêter? (2020–2021), highlights Iranian women practicing a traditional sport despite being banned, embodying themes of liberation and resistance.

Justine A. Chambers’ video installation One hundred more (2024) features mesmerizing, repetitive gestures performed by Chambers and collaborator Laurie Young, inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement and Erin Manning’s idea that small movements can challenge established power dynamics.

The percussive soundtrack of their performance blends with audio from Karen Tam’s immersive installation Scent of Thunderbolts (2024), which explores diasporic memory through archival materials and Cantonese opera elements. Central to Tam’s installation is a stage guarded by a painted tiger and surrounded by fabric bamboo, hosting performances throughout the Biennial.

Elina Waage Mikalsen’s sound sculptures, featured in the Biennial’s second hub at The Auto Building, emphasize music as a conduit for memory. In I Lay My Ear Against the Weave’s Ear (2019–ongoing), she repurposes her grandmother’s weaving tools into musical instruments that produce sounds when viewers interact with their strings, highlighting a connection between weaving and ‘spiritual listening.’

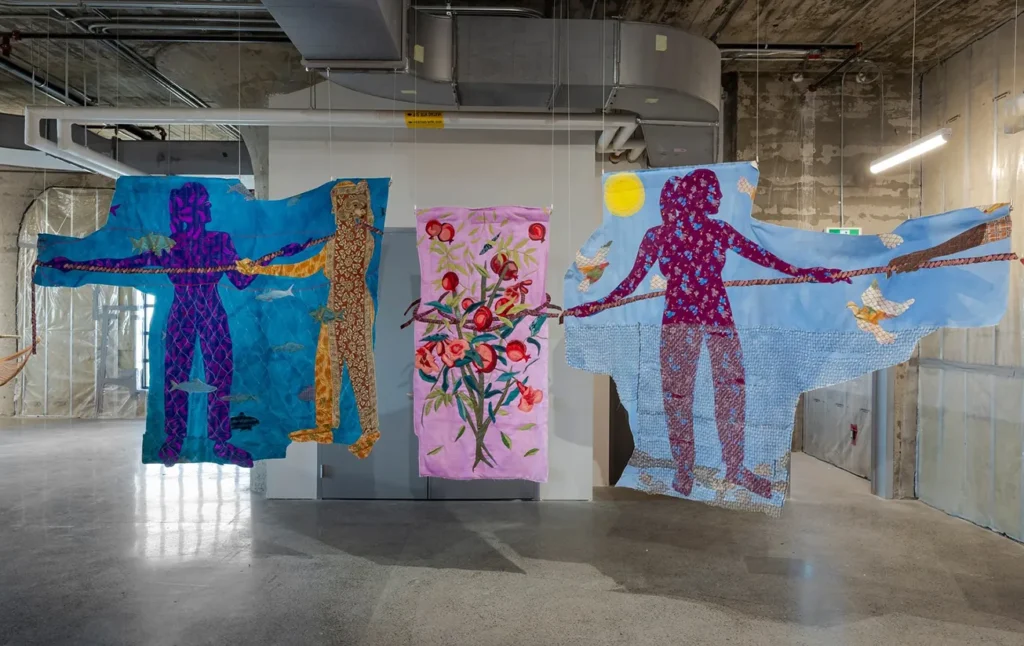

This theme is echoed in Guatemalan artist Angélica Serech’s large-scale textile El viaje de Yibo (Yibo’s Journey) (2024), which spans several meters and employs multicolored cotton threads and traditional weaving techniques to reflect the emotional impact of forced Indigenous displacement.

Stina Baudin’s textile works weave together ancestral knowledge and survival narratives. In her hanging sculpture Data Studies: Caribbean-Canadian Geographies 86/96 (2022), abstract squares of color visualize data on the migration paths of Black Canadians.

Highlighting Toronto’s multiculturalism, Sameer Farooq’s Flatbread Library (2024) is a floor-to-ceiling sculpture that maps local histories through flatbreads from neighborhood bakeries. This work invites visitors to engage with history by consuming the archive, blending cultural preservation with the act of eating.

Engaging with the Biennial in its third iteration feels refreshing, with its sincerity and focus on accessibility as standout strengths. The centralized exhibition venues this year mark a significant improvement over previous editions, which were located in harder-to-reach suburban areas.