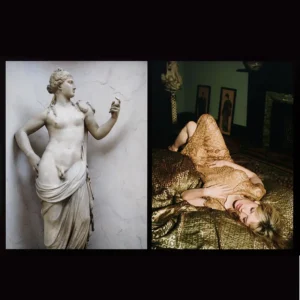

The MoMA retrospective of Thomas Schütte features 100 striking works. The artist moves beyond Minimal and Conceptual styles to reintroduce narrative, blending personal and historical stories that challenge norms and refresh traditional genres.

Curated by Paulina Pobocha, the exhibition reframes perceptions of Schütte’s work, even for those who may not have viewed him as deserving of a MoMA retrospective. Despite notable accolades like a Golden Lion at the 2005 Venice Biennale, Schütte’s art has often been perceived as overly ambiguous or corny.

Thomas Schütte is primarily a sculptor who explores a single subject from multiple perspectives. Engaging in various disciplines—drawing, painting, printmaking, installation, design, and architecture—he does not prioritize any one medium.

Schütte emphasizes the open-ended nature of his exploration, stating, “But what it is I don’t know. As soon as you define it, it’s ended.” Resisting a signature style, he draws inspiration from diverse sources, including Conceptual art, classical statuary, modernist sculpture, theater design, and narrative film.

Schütte’s work often conveys a sense of muteness, likely shaped by his upbringing and Minimalism’s rise. A key moment was his visit to Documenta IX, where Richard Serra’s steel sculpture left a lasting impression.

He studied at Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, where he created Amerika (1975), a piece with dense pencil marks reflecting a void and the failed promises many Germans felt at the time. Post-reunification, his United Enemies sculptures (1993–94) symbolized the tension between East and West Germany, but Schütte frames them as allegories of lingering fascism, resisting simple interpretations.

Schütte’s time studying under Gerhard Richter led to pieces like Große Mauer (1977), abstract paintings resembling a wall that critique the structures of the time. His Vater Staat (2010), an armless man recalling Soviet monuments, and Modell für ein Museum (1982), a furnace-like structure, reflect the darker themes in his work, influenced by his father’s past in Hitler’s army.

The exhibition closes with Schutzraum (1986), a concrete shelter offering no refuge, accompanied by unsettling sounds. Schütte’s art embodies the somber mood of postwar Germany, leaving interpretation to the viewer.

In the exhibition catalog, Marlene Dumas shares her evolving appreciation of Schütte’s art, highlighting their shared generation and experiences in the art world. She recalls her initial confusion over his colorful, seemingly simple aquarellen in 1987, which contrasted with the allure of the Transavanguardia artists.

Over time, she has come to recognize the depth in Schütte’s work, noting his distinct focus on architectural contexts, and his exploration of themes like melancholy and displacement, as seen in installations like the ceramic figures in “Die Fremden”.

Their ongoing dialogue, including a discussion on public sculpture, underscores Schütte’s critical perspective on contemporary art practices, revealing Dumas’s deepening understanding of his artistic vision and its broader societal resonance.