A retrospective of Maria Blanchard, a prominent yet overlooked figure in the Cubist movement, is currently on display at the Picasso Museum in Málaga, Spain. The exhibition highlights the innovative formal complexity, social involvement, depth of symbolism, and inventiveness of her work.

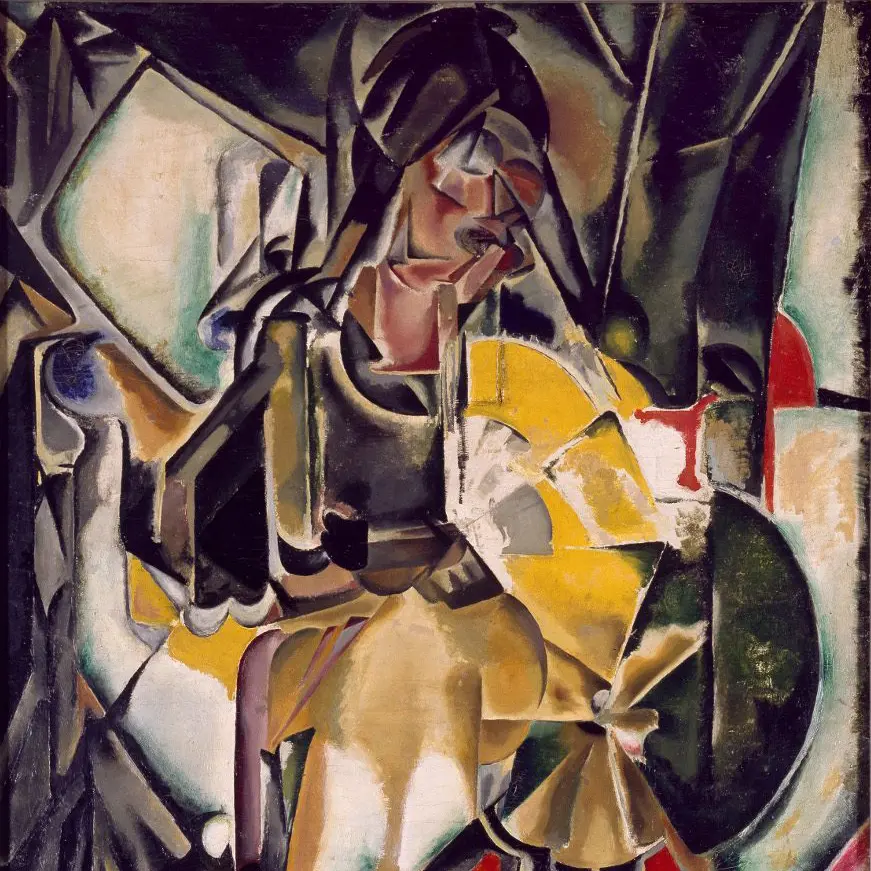

Born in Santander in 1881, Blanchard was inspired by her parents to become an artist. She studied in Madrid and then Paris, where she fell in love with Cubism and the avant-garde art movement. She joined the Section d’Or group, shared a studio with Diego Rivera, became friends with Juan Gris, and produced vibrant, collage-style Cubist paintings of modest still lifes and feminine themes.

In the 1920s, Blanchard’s painting transitioned from Cubism to a more figurative style that explored topics of gender, race, national identity, and socioeconomic class while concentrating on the human condition, especially as it related to women and children. Her paintings frequently emphasized individuals of color or members of the working class, showcasing her aesthetic perspective. She made a name for herself in the 1920s by collaborating with Frank Flausch and the dealer group Ceux de Demain.

One of Blanchard’s most well-known pieces, “Girl at Her First Communion”, is a melancholy depiction of a girl’s rite of passage into womanhood. Originally shown at the Salon des Indépendants in 1920, it is currently housed in the Reina Sofía Museum in Spain. That year, her art was also included in Barcelona’s French Avant-Garde Art exhibition.

Blanchard was a talented artist. Critics praised her much. However, only a few committed collectors were left to carry on her legacy following her death in 1932, and her reputation faded until the late 20th century.

Her first formal acknowledgement came in 1982 at the Museo Español de Arte Contemporáneo in Madrid. She then had retrospectives at the Fundación Botín in Santander and the Reina Sofía in 2012.

A Painter in Spite of Cubism, the current exhibition, aims to highlight her contributions to modern art by showcasing her symbolic richness, social engagement, and creative processes, while also restoring her rightful place in art history.