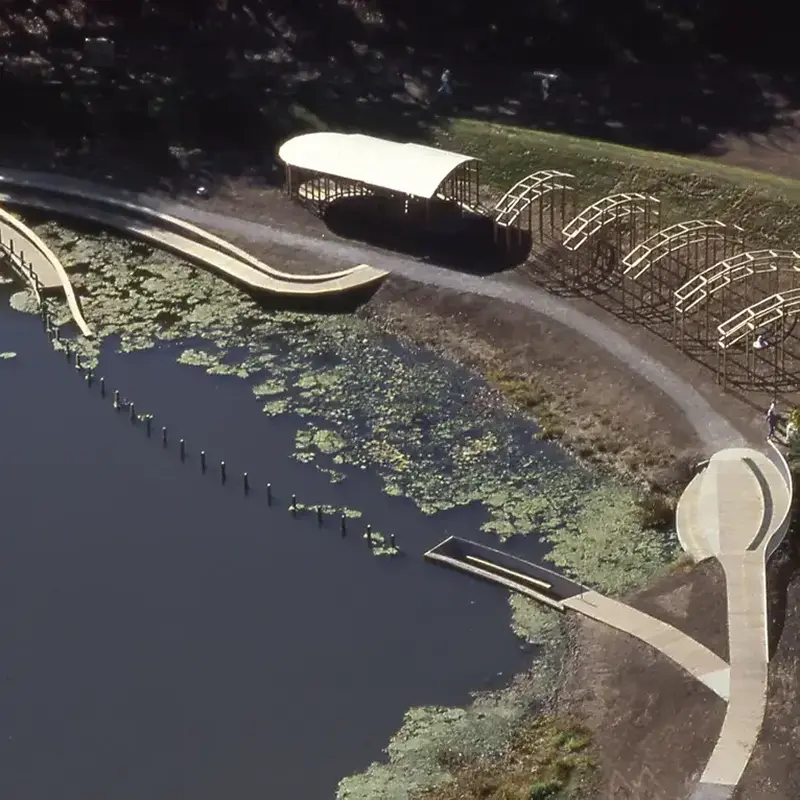

The debate surrounding the Des Moines Art Center (DMAC) in Iowa’s decision to demolish a site-specific installation due to safety concerns continues. An environmental intervention by pioneering land artist Mary Miss, the work has been a part of Greenwood Park for nearly 30 years and is considered the first urban wetland project in the United States.

Commissioned by the museum and built between 1989 and 1996, “Greenwood Pond: Double Site,” consisting of a curved boardwalk, pavilion, and other structures, was designed to provide visitors with an immersive experience in nature.

The decision to remove it due to a safety hazard is complicated by the site-specific nature of land art, where altering or removing the artwork is considered equivalent to destroying it. Critics have expressed dismay at the decision, emphasizing the breach of faith with both the artist and the public. The DMAC justifies its decision, citing safety concerns. However, Mary Miss, the artist, is opposed to the demolition and claims that the decision was abrupt and lacked proper communication.

Art Center Director Kelly Baum addressed ongoing maintenance issues in an “Open Letter” following public outcry. The installation has faced structural challenges and weather damage since its inception, leading to a tipping point in October. A structural engineer’s report identified dry rot, requiring immediate action for public safety. The estimated cost for redesign, re-engineering, and perpetual maintenance is $8 million, beyond the museum’s modest resources.

The Cultural Landscape Foundation (TCLF), an advocacy organization, accuses the DMAC of possible contract violations with Mary Miss. TCLF claims that the DMAC pledged to reasonably protect and maintain the work when commissioning Greenwood Pond, and the plan to tear it down undermines the Art Center’s role as a responsible steward of cultural legacy.

The controversy has also highlighted broader issues, with Miss expressing concerns about gender disparities within the Land art movement, emphasizing the challenges faced by women artists working with the land and the environment and questioning whether the situation would be different if the artist were male.

The clash between art purists prioritizing preservation and pragmatists considering real-world constraints is evident. With Des Moines owning the park, the city’s authority to order removal adds complexity. This case highlights the need to address suitability, durability, and longevity during art project commissioning to prevent future crises.