Frank Stella, an artist who moved American art away from Abstract Expressionism to minimalism, passed away last week at the age of 87. Despite mixed reviews from critics, Stella’s work remains a cornerstone of post-war abstract art.

Stella, who was born in Malden, Massachusetts in 1936, attended Princeton University. Despite his passion for art, Stella pursued a history degree at Princeton, focusing on the Middle Ages. He believed that understanding and respecting one’s rivals is crucial to being a formidable competitor. He also took art history classes, gaining knowledge in European painting and the contemporary New York art scene.

After graduation, he relocated to New York in 1958. He was engrossed in the height of Abstract Expressionism. His Black Paintings from 1958 to 1960 were influenced by the work of Jasper Johns. While these paintings were bold for their time, he continued to innovate, using aluminum paint because it was “cheap and available.”

His minimalist paintings were notably stark, devoid of color, and not designed for visual pleasure. Regarding his work, he once famously commented to Donald Judd, “What you see is what you see.” He continued to reinvent painting throughout the 1960s.

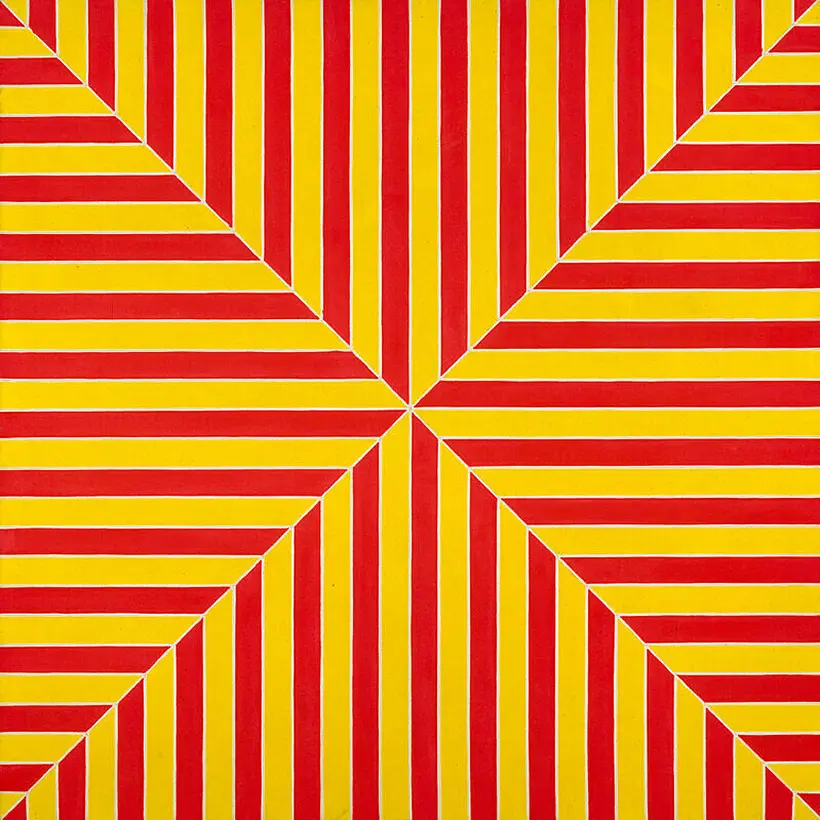

Stella’s earlier works developed into elaborate pieces characterized by vibrant color combinations and intricate patterns. He elaborated that abstract art does not have to adhere strictly to geometric shapes; it can incorporate shapes that evoke narratives or tell stories.

Stella then took a sharp turn, creating unique painting-sculpture hybrids that matched the unconventional shapes of his canvases with chaotic elements. Some pieces included abstract, wave-like components. However, many of his works were less literal. These creations did not sit well with everyone, with some critics accusing Stella of compromising his integrity.

Until his final days, Stella created massive artworks, incorporating digital technology. He would scan objects that caught his interest, enlarging them to monumental sizes. Though some viewed these actions as odd for an artist accused of attempting to end painting, they were unified by Stella’s aim to connect with reality. Discussing his use of aluminum paint, Stella said it was about exploring “the facts of life.”

Marianne Boesky Gallery, representing Stella in New York, commemorated him as a monumental figure in post-war abstract art, noting his work’s exploration of geometry and color, and the interplay between painting and physical form.