Video art can be a difficult medium to grasp and differentiate. It may be confused with art films, as both genres involve moving pictures with artistic endeavors. Video art explores the possibilities of the medium, while film does not.

Even to the most seasoned connoisseur, video art can feel inaccessible as it sometimes melds and works hand in hand with other mediums. On top of that, ownership complexities around replicable files had once contributed to art collectors’ reservations in the early years of the medium. But in an ever more digitally savvy world, is video art reaching its zenith?

In this article we will delve into what video art is, its history, and evolution. We will examine where the future of this medium is heading in a culture heavily entrenched in moving pictures and digital artworks.

What is video art?

Video art uses audio-visual technology to generate and manipulate moving pictures to create artwork. It can weave in other art forms such as dance, performance art, music, architecture, and sculpture.

Over the last few decades, the fluid nature of video art and an increased demand for digital art by institutions has attracted artists from many disciplines. Experimental filmmakers, choreographers, performance artists, photographers, sound and conceptual artists have gravitated to the medium.

How Does Video Art Differ from Film?

Both film and video art use experimental techniques. Being more reliant on narrative, film uses moving pictures to tell a story. Video art, on the other hand, uses moving pictures for pure artistic expression.

Most cinema, including the art-house variety to some extent, has commercial interests. It is reliant upon financial backers that all have a “say”. This can influence the finished product and impact a director’s artistic vision. Meanwhile, video art is traditionally not reliant on narrative and the specter of commercial appeal is not as present. This allows for an unfettered artistic vision to evolve.

The History and Evolution of Video Art

Video art started in the 1960’s, emerging from the Fluxus movement which consisted of a network of international avant-garde artists and composers. They shared the common goal of creating “anti-elitist” and “living art,” as outlined in their manifesto penned by the movement’s founder, George Maciunas.

The introduction of Sony’s portapack video camera in 1965 made the video production affordable. The camera was easy to use and removed the need for a film crew. Inspired by the art films of the Surrealists, Dadaists, and Italian Futurists, artists began to use video as a means for artistic expression.

One of the earliest examples of prominent video art is Bruce Nauman’s Art Make-Up (1968). In the video, the artist applies different colored paints onto his torso with the idea that he is making himself up for the viewer, touching on themes of disguise, masquerade, and reality. His video installation showed footage of all four different paint applications separately on four walls of a square room.

In the wake of the birth and dispersion of television, early video artists explored its impact on society. Nam June Paik, considered the “father of video art,” is well-known for such themes. His work entitled TV Garden (1974-77), is an installation piece containing forty television sets intermingled with plants. In this piece, Paik looks at the tension between nature and technology as humans increasingly create and reside in digital worlds.

Video art was embraced by performance artists using accessible video technology to create records of their work. Famed performance artists Marina Abramovic and Ulay used video technology to record their performances, such as Light/Dark (1977).

While some artists experimented with new editing tools to create flashy imagery, which also changed the music video industry with the emergence of MTV, others used the medium to present social commentary. Howardena Pindell’s epic video Free, White and 21 (1980) is a pioneering example of activist video art that entails the artist describing racial anecdotes and scattering footage of symbolic performance art by herself.

In the 1980’s and 1990’s innovations in technology created more opportunities for experimentation. Artists such as, Bill Viola, experimented with bolder installation pieces. His famed work, The Sleep of Reason (1988) engulfs viewers in nightmarish images that flash across gallery walls unexpectedly.

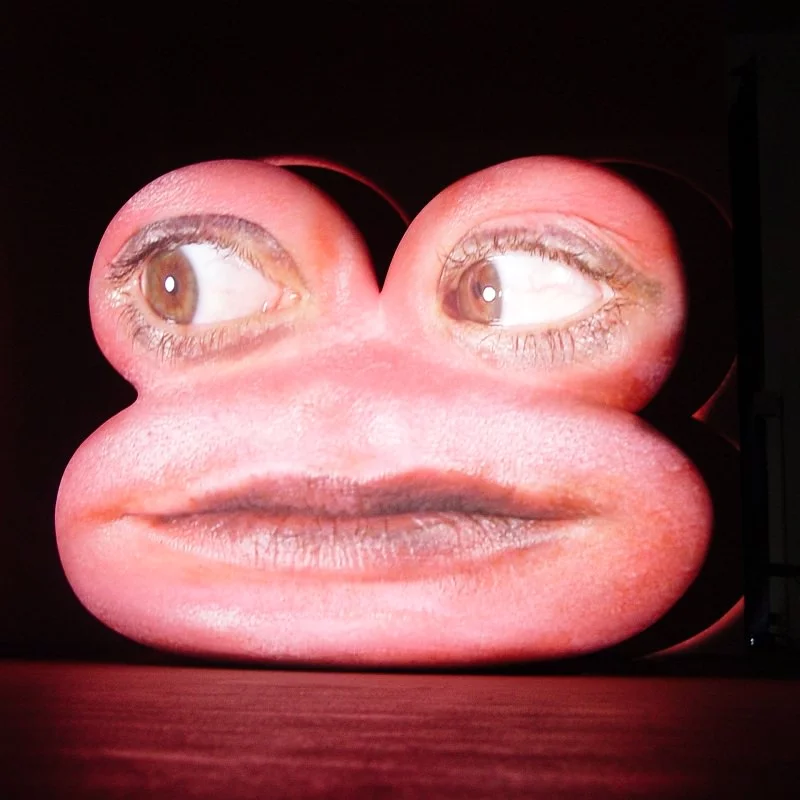

As with Bill Viola’s work, video artists often experiment with space. Works are projected onto architectural or sculptural surfaces, if not viewed through screens. In the 1990’s, Tony Oursler became known for creating footage of eerie faces with giant eyes and mouth specifically designed to be projected onto his nebulose sculptural pieces.

As the digital palate of society matured in the 2000s, galleries and collectors gravitated to video art. Several major museums such as the Tate have amassed impressive video art collections.

Digital editing software became more accessible, allowing video artists to incorporate more sophisticated editing and special effects into their work. Ryan Trecartin’s A Family Finds Entertainment (2004), highlights this with a collage of pop and youth culture influences pasted together by frenetic editing techniques.

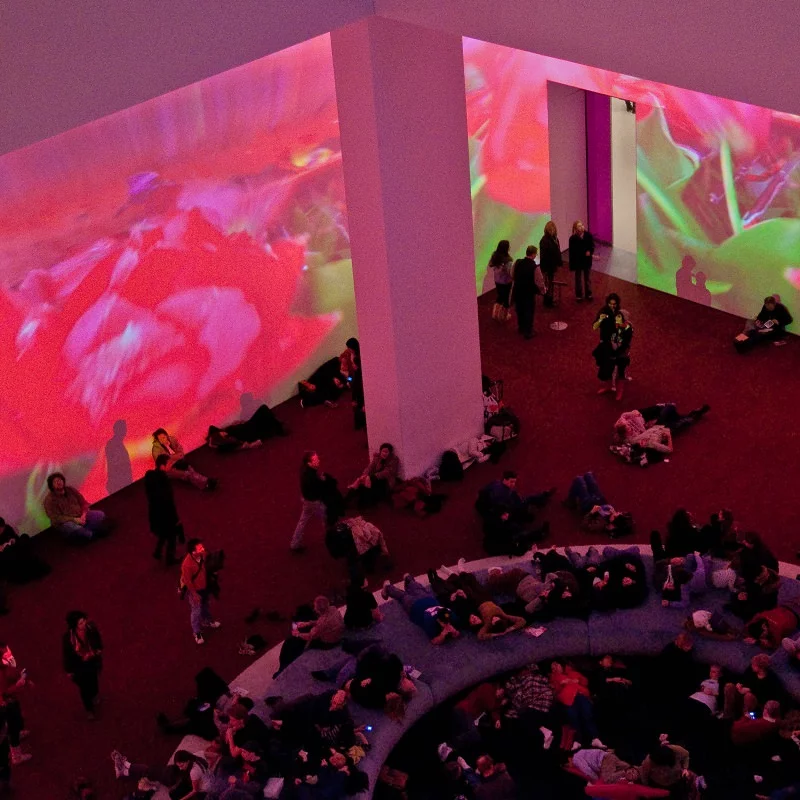

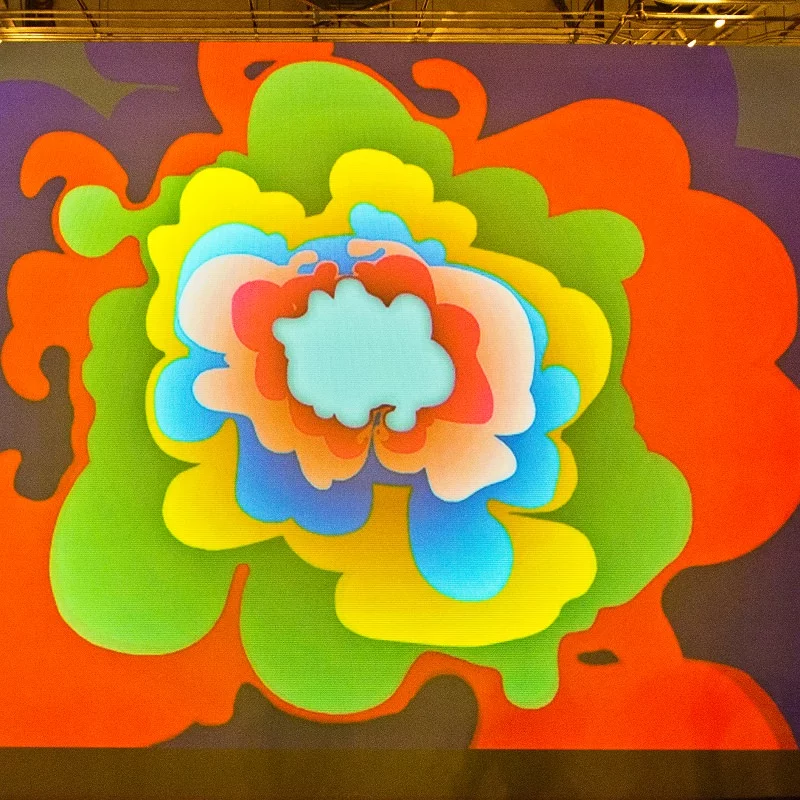

Other artists have started to design immersive art experiences in the early 2000s with their videos enveloping art spaces. One of the first of its kind, Pipilotti Rist’s 2008 piece Pour Your Body Out (7354 Cubic Meters) wrapped around the 25 feet tall walls of MoMA’s atrium. The video displayed footage of ripe apples, vivid tulip fields and luscious strawberries among others that symbolize earthly pleasures.

Pipilotti Rist is also well-known for her conceptual video performances. Open My Glade (2000), which was displayed in Times Square billboards (between 2000-2017) showed the artist smudging her face against the screen as if she is trapped behind the glass and playing around.

Another video performer, who uses herself as the protagonist in her feminist videos is Kate Gilmore. The artist is known for creating and attempting physical obstacles in her video performances, representing women’s real-life struggles. Her piece Between a Hard Place (2008) is in the collection of MCA Chicago.

Not all video performances demand a human main character. We also see video performances where the objects reveal the conceptual message. In Ash Ferlito and Matt Taber’s Breakfast in America (2012), the color spectrum is broken down by tableaux of everyday objects arranged according to their hues. The objective behind this fast paced, single shot video performance is to show the linguistic relationship between objects.

Video Art and the Interplay with Technological Advancement

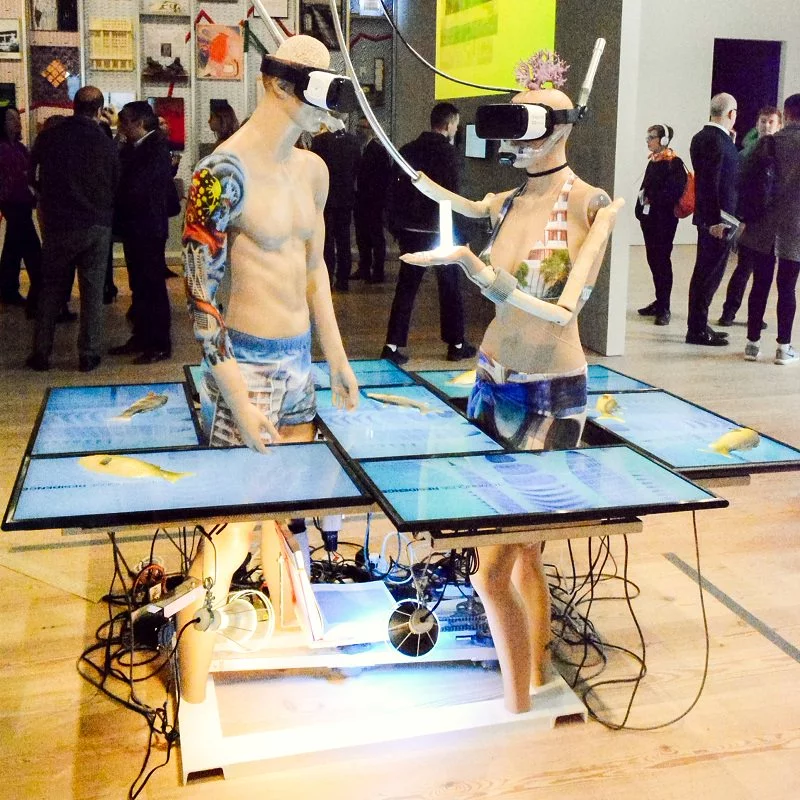

Technology has undergone a meteoric expansion within modern society, enabling video art to blend with the disciplines of architecture, digital art, video games and virtual reality. Contemporary video art’s foray into virtual reality expands upon the immersive experiences created by installation pieces.

Many video artists have embraced virtual reality as the technology improved from the clunky 90’s version. Multi-media artist Jacolby Satterwhite creates lush VR dreamscapes in his video art and music videos that carry on the visual language of video games.

During the pandemic, video artists embraced social media to engage with audiences. But this has exposed issues with these platforms, raising questions around privacy, censorship, and the undue influence they have on our lives. Furthermore, with Meta (formerly Facebook), announcing their plan to immerse us in virtual worlds, we can predict that virtual reality video artwork is set to increase in demand.

The juxtaposition of the freedom and control created by the expansion of technology is a theme video art has explored repeatedly. The work Deep Contact (1984-89) by Lynn Hershman Leeson, examined this back in the 80’s, showing the somewhat prescient nature of the medium. Deep Contact is an interactive video/multi-media installation which examines how technology can manipulate behavior.

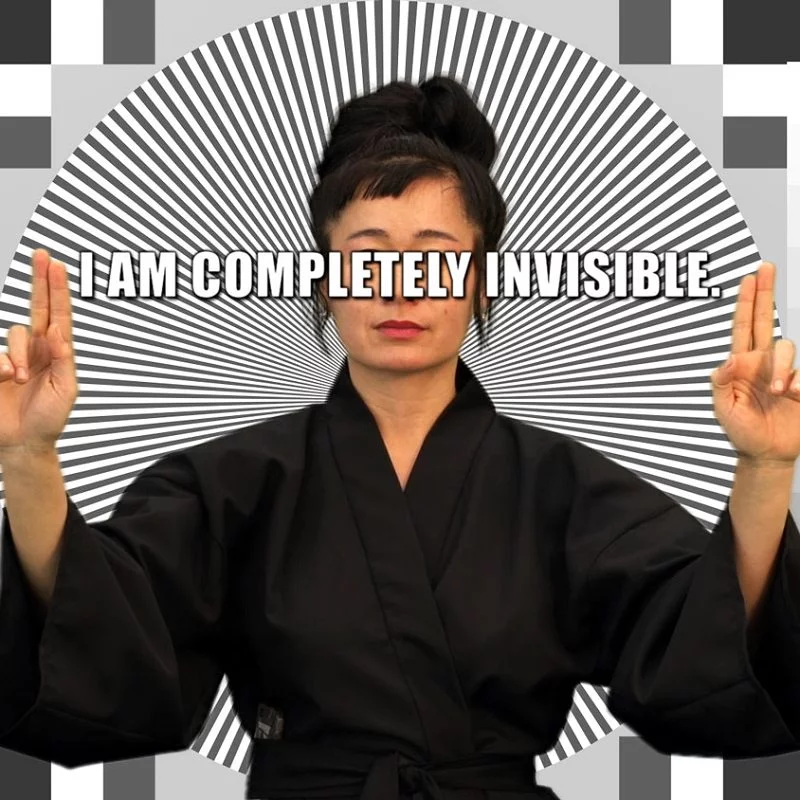

Hito Steyerl’s work, How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (2013), examines the constant surveillance of civilians that has been facilitated by modern technology.

Video Art’s Future and the Brave New World of NFTs

NFTs (Non-Fungible Tokens) have exploded in the art world. And with video art being a medium that has always flirted with technological advancements, many artists are exploring how to leverage this technology. With historic reservations from collectors regarding the replicability of video art, artists have been using NFTs to avoid ownership and authentication hurdles of the past. NFTs allow artists to provide collectors with more sophisticated ways to track original file ownership using blockchain technology.

Thematic Resonance of Video Art with Modern Times

As a society we are becoming more enmeshed with the digital world, including in our art. When you consider that video art has traversed these themes since the 60’s, its relevance, is clear. The uptake in video art sales and NFTs speak volumes. The more technology infiltrates our everyday lives, the more these artforms speak to us. We are more comfortable with electronic scapes and digital ownership than ever before.

From its birth in the mid-60’s to the VR landscapes of today, video art has always exhibited a future focused lens. As a medium, it has openly experimented with and embraced innovative technologies, facilitating the invent of moving and immersive art. This willingness to enfold with modern technology, and open examination of how we interact with it, is what has allowed the medium to flourish over decades.

Video art’s exploration of the modern relationship between nature and technology is poignant. We are living it every day.